One of the main challenges I will have to face during my journey as a type 1 diabetic is the logistics around the supply and conservation of insulin. Indeed, while insulin can be found 24/7 in nearly all pharmacies in the western world, finding insulin in Africa is another story.

In a few words, insulin, like many injectable medications or vaccines, needs to be kept at a controlled temperature in order to keep its efficacy. Subject the insulin to temperatures below 2°C or higher than 8°C and the molecules composing the active substance and/or the adjuvants may break down or associate and render the medicine ineffective or unreliable. As a result, I would get high blood sugar levels.

A complex logistics system is hence required to bring insulin from the production laboratory to the patient. This isn’t a problem in the western world as all the needed infrastructures are well in place. Try to do the same in less developed parts of the world, and you will certainly be confronted to important difficulties. Different organizations are trying to tackle the temperature problematic by developing new transportation procedures, systems and equipments, while others are doing research in the hope of, one day, making it possible to administer insulin and other medications in another way than through injections. Things are moving in the right direction on several fronts, yet a great deal of work still lays ahead.

So while the capitals and the big cities throughout Africa have infrastructures able to comply with high levels of requirement, the temperature controlled chain of supply will most probably be broken from that stage on. This is certainly true in remote parts of certain countries, or in areas where the electric power supply is subject to interruptions or simply broken or absent. And even if the power-grid is functioning, you need, as a patient, to have the financial resources to have a fridge at home to keep your insulin away from the heat. This, of course, is unthinkable for many people across the African continent. Those people are hence, in such conditions, excluded from a reliable treatment and find themselves in a very difficult situation !

The planning

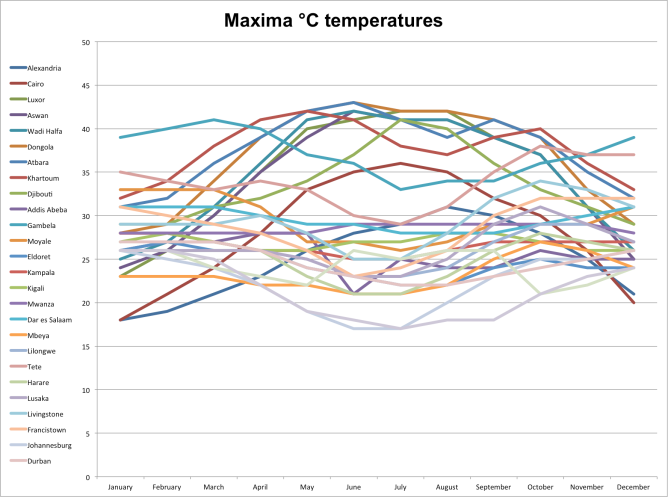

Knowing I will have to face such a difficulty, I need to find out about the temperatures I will be confronted to, at which moment of the year and in which areas these will occur. To do so, I collected data about the maxima, minima and average temperatures per month in the main towns I am planning to cycle through. All in all, I ended up with about 1,000 entries that I translated into several graphics. It looked… colourful and artistic. Which was nice, but not very helpful.

This is where my friend Ryan McKenna offered his help. Being a marine scientist who develops and creates maps and cartographies for his work and studies, Ryan kindly offered to help create the maps I desperately needed. I transferred him the data I had collected and he looked up other sources he was familiar with in his field of work. The result ? A set of maps especially created for Bike with Diabetes, compiled into a GIF : precipitations and average temperatures on the African continent.

Brilliant ! I now have a dynamic tool to project myself in space and time instead of loosing myself in confusing colourful lines.

The first and most important information that this map brings out is that whatever the route or the period I choose to start cycling, I will, somewhere, at some point, be confronted to high temperatures on my route. This means that I need to be equipped and be prepared to confront myself and my insulin to such conditions.

The second teaching is that I have a 3 months slot between late October and late January to cycle the circa 4,000 km that separate the warm lower fields of the Nile Delta and the cooler altitudes of the Ethiopian plateaus. Given that information, I have to make sure I will be in Alexandria by the end of October 2017 and in Gondar or further in Ethiopia by the end of January 2018.

Now that I know what I may be confronted to, I need to find out a way to make my journey possible, despite the climatic and meteorological conditions and despite the supply and conservation difficulties. In other words, I need to choose the right equipment to transport my insulin and make sure I will be able to get medical and insulin supplies on a regular basis, about every 4 to 6 weeks.

Feel welcome to point me in the right direction in the choosing of the appropriate gear on Twitter, Facebook or in the comments bellow the post.

Last year I rode across the USA during the summer and into the fall (June 21 – October 23). I kept my insulin in a Large Frio Wallet – http://www.frioinsulincoolingcase.com/frio-large.html. This worked perfectly. The key is to make sure you don’t over soak the wallet as the crystals will swell to the point that you can’t get the insulin vials/pens in the wallet. Also the wallet should be in a place where air can flow over it, as opposed to trying to store it inside an enclosed dry bag or cooler.

Cheers,

Mike

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank your for sharing your experience Mike !

Frio coolers indeed seem to be the most convenient system and are hence on my shopping list for in-use insulin, yet I will need to use a more “efficient” cooling system for my stored supplies and during at least two stages of my journey due to temperatures that will probably be higher than 38°C (between Khartoum in Sudan and Gondar in Ethiopia, as well as on the border area between Ethiopia and Kenya). This is because the Frio system will keep insulin between 18 and 26°C in air temperatures up to 38°C and maxima temperatures in the shadow in those 2 areas are estimated to be around 32-33°C when I’ll be cycling through them. So probably above 38°C while cycling in the sun.

Where/how did you store your Frio packs on your bike while cycling in order to allow a constant evaporation ?

I hope you have other cycling plans coming up this summer !

I wish you all the best,

Arthur

LikeLike

Arthur,

I carried my frio wallet in a mesh part of my handlebar bag. Sometimes I moved it to a mesh part of my side pannier. I did this to move the frio away from direct sunlight in the afternoon. Mostly though, I made sure it was wet each morning and then forgot about it.

In some areas where it was quite hot, I was able to soak the frio in cold water. I think this kept the insulin at a cooler temperature, but I can’t guarantee that since I did not carry a thermometer to read the temperature inside the frio.

How long do you think you will be in areas where the temps will be above 38C? My experience has been as long as it is not a prolonged period, most insulins are surprisingly more robust than their label would suggest. I lived on a sailboat for 5 years traveling in pretty warm tropical climates. During that time, I had my back-up insulin refrigerated on the boat, but was out with insulin in my pump for many hours. I really never experienced a problem (being careful at the same time though!).

My last bike trip was 4 months and I did purchase two vials of insulin along the way from pharmacies that had proper refrigeration. This year we are going to ride from Vancouver Island, BC Canada and then down the US Pacific Coast to Los Angeles.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the info Mike !

I was told by my doctor that I could keep my in-use insulin at 30°C for up to 2 to 3 weeks and that if that would be the case, I would have to pay extra attention to its efficacy. But my back-up insulin should always be kept at a much lower temperature.

The amount of time I will be cycling in high temperatures is a bit difficult to predict now as this would depend on multiple factors : weather at the moment I will be cycling, chosen itinerary, state of the road, etc… This said, my estimate would be about 4 to 5 weeks in the Sudan-Ethiopia leg and about the same on the Ethiopia-Kenya border area (see red coloured area on the GIF).

The Vancouver – Los Angeles route seems to be amazing! I have a friend who is cycling from Los Angeles to Seattle at the moment. Who knows, you might meet on the road ? Here is her blog, just in case : http://www.survivaltour.org/home

LikeLike